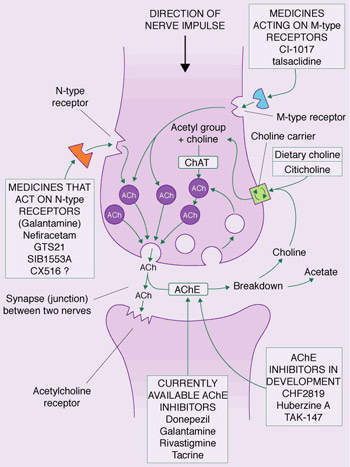

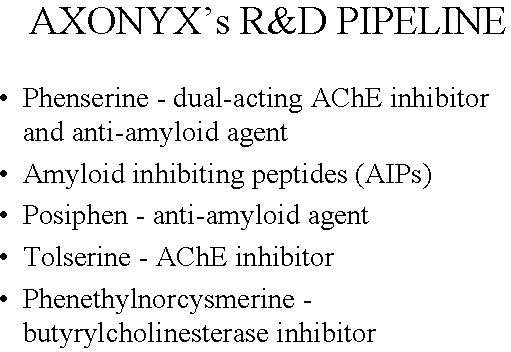

Axonyx, a US biopharmaceutical company that focuses on treatments for dementia, developed phenserine as a next-generation acetylcholinesterase (AChE) inhibitor indicated for the treatment of Alzheimer’s disease.

Phenserine was licensed to QR Pharma, a startup biotechnology company, after Axonyx merged with TorreyPines Therapeutics in 2006. In May 2009, QR Pharma decided to stop the production of phenserine, after it failed in Phase III of its development. The drug, its patents and the material stored in a number of locations were withdrawn in May.

From the original NIH technology, QR Pharma retained the two follow-on compounds, posiphen and bisnorcymserine.

Unlike other marketed AChE inhibitors, phenserine was supposed to have a dual mechanism of action that also included anti-amyloid activity, which could confer disease-modifying effects in patients with Alzheimer’s disease. If it were substantiated in an ongoing clinical trial then phenserine would have opened the door to an entirely new type of treatment for the Alzheimer’s.

Phenserine was Axonyx’s lead investigational compound in a series of drugs under development for the treatment of Alzheimer’s disease and other types of dementia.

QR Pharma is currently evaluating posiphen, one of the two follow-on compounds of phenserine, in clinical trials. The company has also been awarded a patent for the use of posiphen to treat cognitive impairments related to Down’s Syndrome.

New treatments needed to halt rising prevalence of Alzheimer’s disease

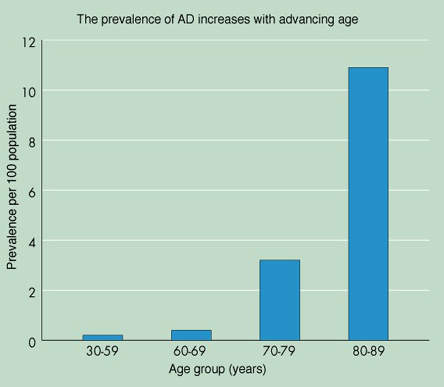

It is estimated that between 12 and 15 million people worldwide have Alzheimer’s disease, with 4.5 million people affected in the US alone. Because Alzheimer’s is primarily a disease of age, these figures are projected to rise significantly as the proportion of elderly people in the world’s population increases.

Indeed, by 2025 there are likely to be more than twice as many people with Alzheimer’s disease than there are today unless more effective treatments are discovered. Among those aged 85 years and older, the prevalence of Alzheimer’s disease may be as high as 50%.

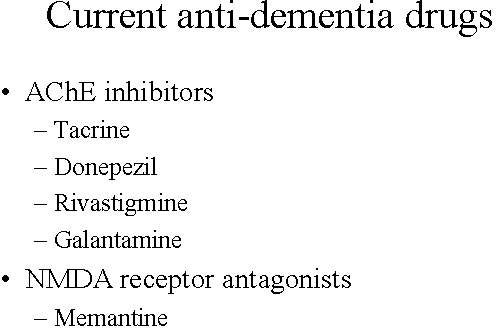

Current anti-dementia drugs provide modest symptomatic improvement, but do not address the underlying pathology of the disease. Furthermore, their effect on cognition, executive functioning and behaviour are only temporary. None of them are considered to have disease-modifying effects that can halt the progression of the disease and stop cognitive decline – the hallmark of Alzheimer’s. Many patients also fail treatment with first-line anti-dementia drugs because of poor efficacy, safety and adherence to treatment.

There is an urgent need to find drugs that can address the underlying pathology of Alzheimer’s disease and help halt the inexorable rise in the prevalence of the most common form of dementia to afflict the elderly.

Anti-amyloid agents may have disease modifying effects

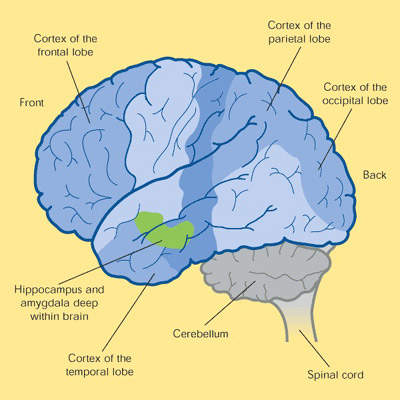

At post-mortem, the brains of patients who have died from Alzheimer’s disease have a number of distinct pathological features: amyloid plaques, neurofibrillary tangles and a loss of cortical neurones and synapses.

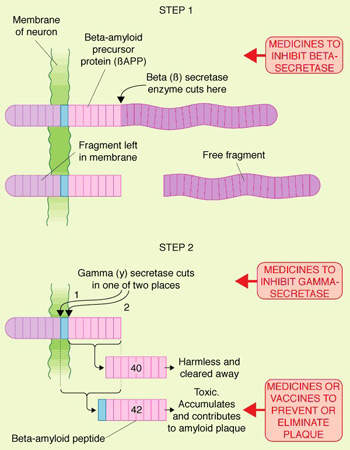

The discovery that the amyloid plaques in the brains of Alzheimer’s patients contained an accumulation of insoluble toxic beta-amyloid (?-amyloid42), derived from amyloid precursor protein, led to the search for compounds that could either prevent the deposition of toxic beta-amyloid in the brain or eliminate existing amyloid plaques.

After drugs that target cholinergic neurotransmission, anti-amyloid therapies represent the next largest group of compounds in development for Alzheimer’s. The hope is that by targeting what is believed to be a key step in the pathogenesis of the disease, such compounds will have a disease-modifying effect.

Clinical trials of phenserine

Early evidence of clinical efficacy, safety and tolerability was demonstrated in a Phase II randomised, double-blind and placebo-controlled trial in the US that involved 72 Alzheimer’s disease patients. The trial, completed in 2001, showed that phenserine was well tolerated, with a lower incidence of adverse events than traditionally seen with marketed AChE inhibitors: the incidence of nausea and vomiting with phenserine was less than 8.5%.

The rapid clearance of phenserine from the blood may account for its improved tolerability. Although not adequately powered to assess efficacy, the trial nonetheless provided evidence that treatment with phenserine improved cognition, memory and functioning in Alzheimer’s patients.

Phenserine underwent evaluation in a Phase IIb trial and two Phase III registration trials, designed to assess its ability to lower levels of beta-amyloid precursor protein and beta-amyloid in the plasma and cerebrospinal fluid of patients with mild to moderate Alzheimer’s.

In the Phase III randomised, placebo-controlled double-blind studies the safety and efficacy of phenserine (10mg and 15mg twice daily) was evaluated in 375 and 450 patients respectively with mild to moderate Alzheimer’s. However, phenserine failed in Phase III development.

Clinical trials of posiphen

In the Phase Ia study, 60 patients were administered single doses between 20mg and 160mg on a daily basis. In the Phase 1b study, posiphen was tested on patients who were given oral doses of 20mg, 40mg and 60mg. The treatments involving 20mg and 40mg were tested for seven days, while the treatment using 60mg continued for ten days. On the first and last days, single doses were given to establish the drug’s pharmacokinetics.

Higher posiphen doses were found to result in incidences of adverse events of mild or moderate severity. After oral administration, posiphen was found to be absorbed quickly and Cmax was achieved within 1.2 to 1.5 hours. The Cmax did not increase in proportion to the dose given. QR Pharma has found posiphen to be safe for continuing development.

Before starting the Phase II trial on posiphen, QR Pharma has to determine whether the two mechanisms that posiphen showed in human tissue culture cells and in mice will be effective in humans at reasonable doses.

In April 2009, QR Pharma received an investment of $500,000 to further the clinical development of posiphen from Ben Franklin Technology Partners.

In February 2010, QR Pharma announced the initiation of another Phase I trial of posiphen in early-stage Alzheimer’s disease patients. About 30 patients are expected to be recruited for the study, which is scheduled for completion in September 2010.

Marketing commentary

The current market for anti-dementia therapies is in its infancy with among the highest growth dynamics in the CNS market, fuelled by a growing elderly population and the need for better treatments.

The failure of phenserine to progress past Phase III clinical trials was a disappointing result for the companies involved and the industry. However, it is hoped that its follow-on compound posiphen will produce favourable results as it continues into Phase II trials and hopefully beyond.